The Bible in Color and Light: An Apologetic for Recovering the Stained Glass Tradition

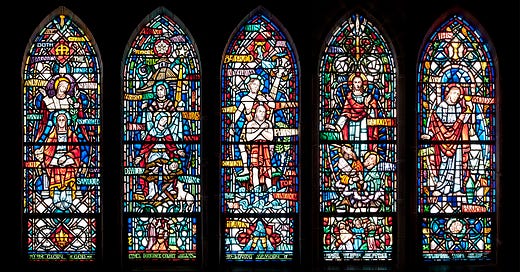

It was my first Sunday morning at the Arctic Warrior Chapel on Fort Richardson, Alaska, but the moment etched itself into my memory as something extraordinary. I was a brand new soldier away from home for the first time, and going to church was something that gave me a much-needed place of comfort and familiarity. The air was heavy with the scent of polished wood and the faint murmur of prayers, a space steeped in reverence. As I sat in one of the pews, my gaze lifted, almost instinctively, to the windows that encircled the upper walls of the sanctuary. It was then that I saw it—the story of Scripture told in radiant color and light.

The windows were a masterpiece of craftsmanship and devotion. Each pane seemed alive, glowing with an inner fire as sunlight poured through. Together, they formed a breathtaking mosaic of the biblical narrative, stretching from the lush green of Eden’s garden to the glorious golden hues of the New Jerusalem. The story unfolded in a sequence of vivid images: Adam and Eve, the Ark, Moses parting the sea, a shepherd with his flock, a cross on a hill, and a Lamb triumphant on a throne.

I sat in awe, tracing the arc of salvation history with my eyes, marveling at how these windows, silent yet eloquent, proclaimed the truths of the Bible. They were more than decorations; they were a teacher, a storyteller, and a guide. For centuries, stained glass had served as the Bible of the illiterate, but even in an age where Scripture is accessible in every format imaginable, their power to captivate and instruct remains undiminished.

There, in that quiet chapel, I felt the weight of history and faith converge. These windows were not mere art—they were catechesis in color, theology in light, and an invitation to meditate on the eternal truths they depicted. Each pane seemed to whisper the words of the psalmist: "Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path" (Psalm 119:105).

In that moment, the Arctic Warrior Chapel became more than a place of worship; it became a portal to the divine. The interplay of light and shadow, of color and story, transformed the ordinary into the sacred. It was as though the very heavens had bent low to touch the earth, and in that meeting of light and glass, the eternal truths of Scripture came alive.

The Origins of Stained Glass in Christian Worship

Stained glass windows are often seen as synonymous with medieval cathedrals, yet their story begins centuries earlier. As Christianity transitioned from a persecuted faith to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, art began to flourish as an expression of worship. By the fourth century, mosaics and frescoes adorned the walls of basilicas, using vivid colors to tell the stories of Scripture to congregations. These early forms of visual storytelling laid the groundwork for the luminous beauty of stained glass.

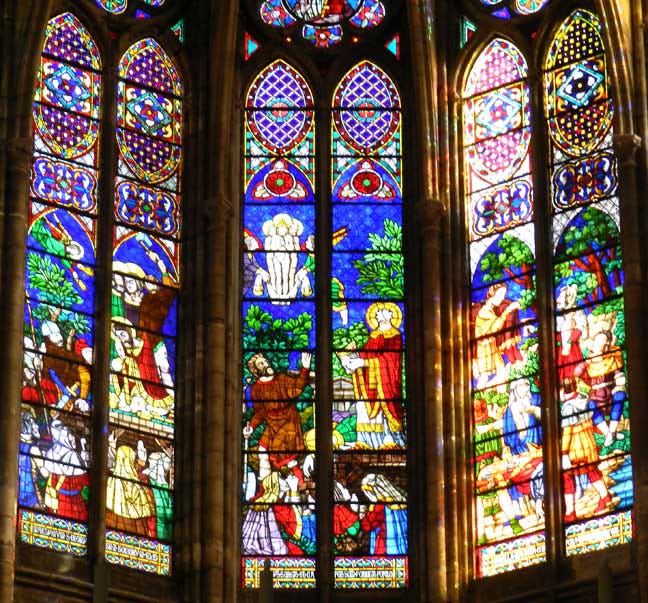

The art of stained glass, as we know it, emerged in the early Middle Ages, reaching its zenith during the Gothic period. The Cathedral of Saint-Denis in France, often considered the birthplace of Gothic architecture, played a pivotal role in this development. Abbot Suger, the visionary behind its 12th-century renovation, believed that light was a metaphor for divine presence. His passion for “lux continua”—continuous light—led to the incorporation of large stained glass windows that transformed the space into a celestial vision. These windows were designed to direct the worshipper’s mind heavenward, illustrating the idea that divine truth illuminates the soul.1

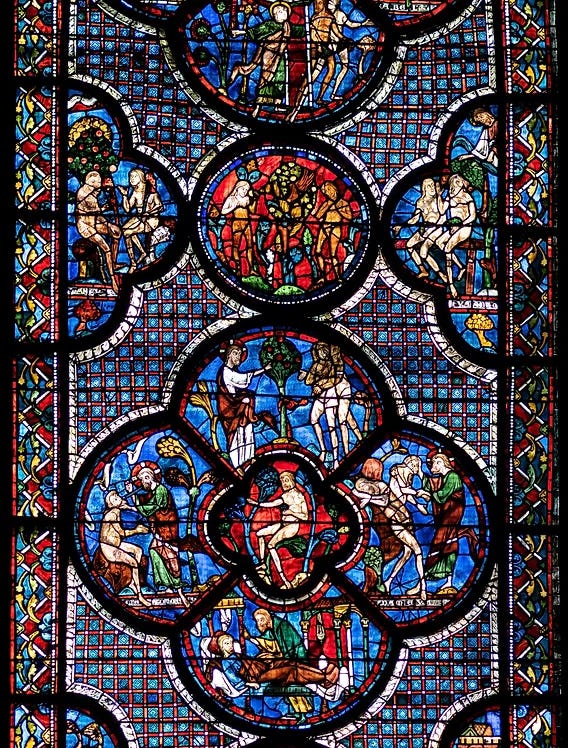

As stained glass became more prominent, it evolved into an essential catechetical tool. In a world where literacy was rare, especially among the laity, the windows served as the “Bible of the Poor.”2 The vibrant depictions of biblical stories and saints' lives offered an accessible way for worshippers to engage with Scripture. Each window was carefully planned, not only to beautify the space but to educate and inspire. For instance, the rose windows of Chartres Cathedral present a visual theology of salvation history, with intricate scenes radiating out from Christ at the center.

This marriage of art and theology was no accident. Stained glass was deeply rooted in the church’s mission to make the truths of Scripture visible and tangible. The light passing through the colored glass symbolized divine grace illuminating the world. As the sun moved through the day, the shifting light created an ever-changing mosaic, reminding worshippers of the dynamic and living nature of God’s Word.

By the late Middle Ages, stained glass adorned churches and chapels across Europe, each window telling stories uniquely suited to its community. While Gothic cathedrals like Notre-Dame de Paris and York Minster showcased the grandeur of stained glass on a monumental scale, even modest parish churches embraced the art form, creating windows that reflected local saints and traditions.

Theology in Color

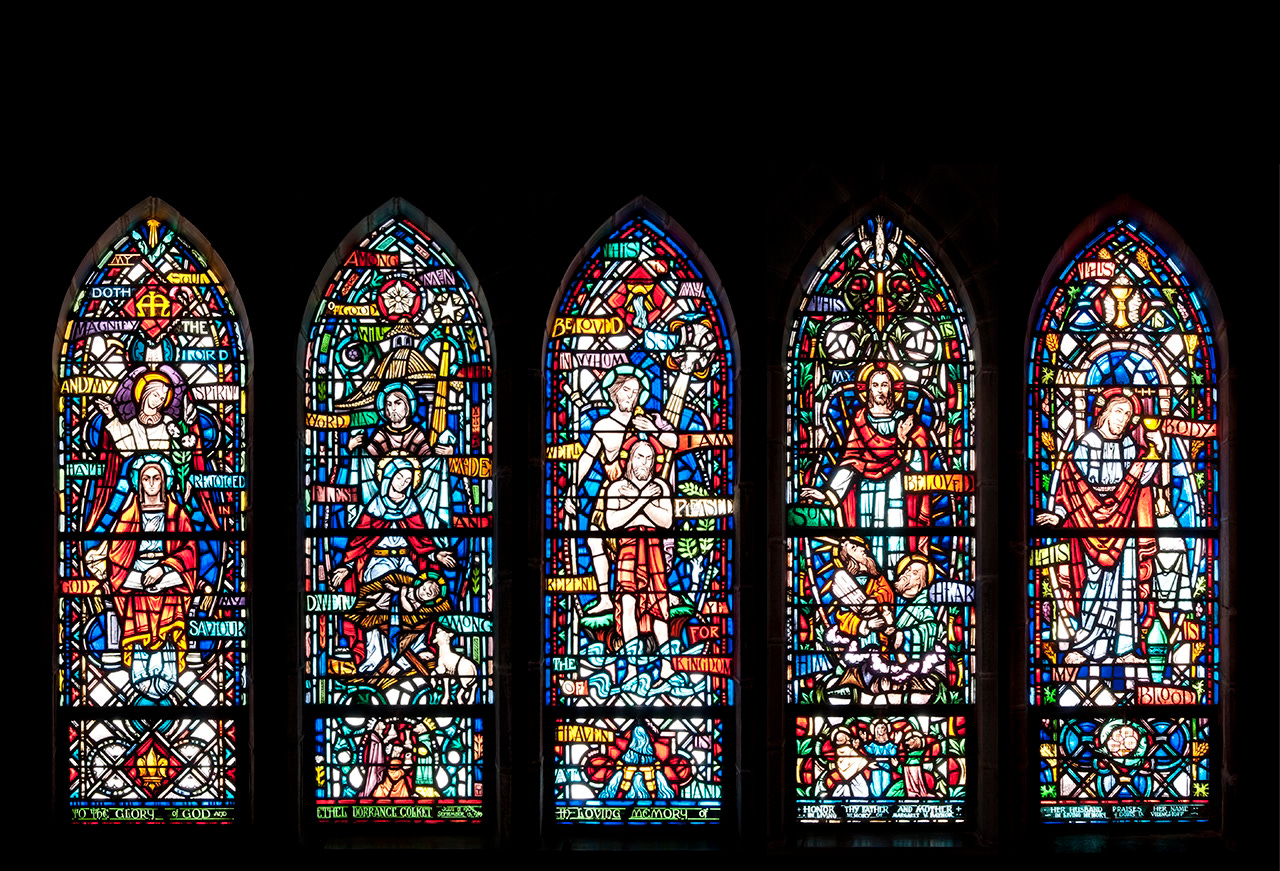

Stained glass windows were more than mere decoration; they were sacred narratives, casting eternal truths in brilliant light and color. They invited worshippers to see the unseen and to meditate on the mysteries of the faith. Each color, image, and arrangement served a purpose, making complex doctrines accessible to all who entered. The light streaming through the glass symbolized divine grace, while the interplay of shadow and illumination reminded worshippers of the eternal struggle between sin and redemption.

The colors themselves carried profound meaning, rooted in the symbolic language of the Church. Blue, for example, was often associated with the heavens, emphasizing purity and divine presence. Red symbolized Christ’s sacrifice and the fire of the Holy Spirit, while green reflected the hope and renewal found in God’s creation. Gold represented divine glory, often reserved for depictions of Christ in majesty.3 This chromatic symbolism ensured that even the illiterate could grasp theological truths through visual cues.

Beyond the colors, the very arrangement of stained glass windows was often a theological statement. Central to many Gothic cathedrals were rose windows, radiating outward with Christ at the center, surrounded by saints, apostles, and scenes from Scripture. This arrangement highlighted the centrality of Christ in salvation history and the unity of all things in Him.

Individual panes within these windows were like pages in a storybook, guiding the viewer through key moments of the Bible. For instance, in Chartres Cathedral, a famous lancet window portrays the genealogy of Christ, beginning with Jesse and culminating in the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child. This visual representation of the "Tree of Jesse" encapsulates the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy in the New Testament.4

Stained glass also served to connect worshippers to the sacred mysteries of the faith. Scenes of Christ’s Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension were designed to evoke both contemplation and devotion. Saints and martyrs, depicted in vivid detail, reminded the faithful of the Church’s triumph over persecution and the hope of eternal life. The windows invited viewers to participate in the grand narrative of salvation, encouraging them to see their own lives as part of God’s unfolding story.

Perhaps most significantly, stained glass exemplified the medieval understanding of the church building as a microcosm of heaven. Abbot Suger’s belief that stained glass could transport the soul to a divine reality is reflected in the words he inscribed at Saint-Denis: “Bright is the noble work; but being nobly bright, the work should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through the true lights to the True Light.”5

Acknowledging a Profound Craftsmanship

The creation of stained glass requires a delicate interplay of artistry and technical skill, with each step imbued with purpose and devotion. The process begins with a design, often sketched by a master artist who collaborates with theologians and clergy to ensure the window aligns with the church’s liturgical and theological vision. This design, or cartoon, is a full-scale drawing that maps out the intricate details of the final piece. The design phase often involved significant theological consultation to ensure each element conveyed the intended spiritual truths.6

Once the design is approved, sheets of colored glass are selected and carefully cut to match the cartoon’s specifications. The glass itself is made by adding metallic oxides to molten sand, a process that dates back to ancient times. For instance, cobalt produces blue, copper creates green, and gold dust imparts a warm red hue. Each piece is meticulously shaped and smoothed, often requiring the skill of experienced glass cutters.7

The next stage involves painting the details onto the glass. Black or brown paint is used to add shading and fine details, such as facial expressions or folds in clothing. This paint, made of powdered glass, iron oxide, and a liquid binder, is fired onto the glass in a kiln, permanently fusing the design into the surface.

Once painted and fired, the individual pieces are assembled using lead cames—H-shaped strips of lead that hold the glass in place while allowing for slight flexibility. The lead framework is soldered at the joints and reinforced with steel bars to ensure the window’s structural integrity. This method, known as leading, has remained largely unchanged for centuries, a testament to its enduring reliability.8

Finally, the completed panels are installed into the church, often with great ceremony. The placement of the window is as significant as its design; east-facing windows, for example, often depict the Resurrection, symbolizing the rising of Christ as the sun rises.

The creation of stained glass windows was not merely a technical exercise but a deeply spiritual act. Medieval artisans viewed their work as a form of worship, dedicating their skills to the glory of God. This perspective is beautifully captured in the words of a 12th-century craftsman: “I labor for eternity. May this work glorify God and speak of His wonders to generations.”9

A Unique Catechetical Tool

From their inception, stained glass windows were designed to do more than adorn church buildings; they were vibrant catechisms, teaching the truths of Scripture and the faith to congregations of varying literacy levels. Each window was an opportunity for the Church to communicate the grand narrative of salvation, making theological truths accessible to all. They provided a way for the Church to reach worshippers who could not read the Scriptures themselves. The vivid imagery captured pivotal moments from the Bible, such as the Fall of Adam and Eve, the Exodus, and the life of Christ, offering a dynamic means to understand God’s work in history.

Each scene was carefully chosen and arranged with pedagogical intent. The windows often followed a logical progression, such as the story of creation flowing into the fall and culminating in redemption through Christ. For example, the windows of Canterbury Cathedral present a unified narrative arc, with scenes from the Old and New Testaments interwoven to highlight the continuity of God’s covenant.

Beyond biblical stories, stained glass also depicted saints and martyrs, whose lives of faithfulness were held up as examples to inspire devotion and perseverance. These windows served to remind the faithful of their connection to the “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1), urging them to live lives worthy of the gospel.

Stained glass windows were not passive displays; they actively engaged the worshipper. Medieval clergy often used these windows as teaching tools, guiding congregants through the stories and symbols during sermons or private instruction. The windows, rich with layers of meaning, encouraged contemplation. A single image could evoke multiple theological truths, such as Christ as the Good Shepherd embodying themes of guidance, sacrifice, and divine care.

The symbolic use of light further reinforced the catechetical purpose of stained glass. Light was seen as a divine presence, illuminating the human soul with God’s truth. When sunlight passed through the windows, it transformed into a kaleidoscope of colors, a reminder of God’s glory breaking into the earthly realm. This interplay of light and color was deeply theological, emphasizing Christ as the "light of the world" (John 8:12) and the Church as the vessel through which His light shines.

The catechetical role of stained glass remains significant even in modern times. While literacy is now widespread, the windows still captivate and teach. They remind worshippers that the faith is not merely intellectual but also experiential, engaging the senses and the imagination. The timeless artistry of stained glass continues to draw hearts and minds upward, offering a glimpse of heaven’s beauty and the enduring truths of God’s Word.

Restoring the Art of Sacred Light

In an age dominated by minimalist aesthetics and sterile functionality, the art of stained glass has too often been relegated to the past, dismissed as an artifact of a bygone era. Many modern churches, in their pursuit of practicality, have stripped their sanctuaries of the beauty and richness that once made these spaces windows into the divine. Yet, the loss of stained glass—and the visual theology it represents—has impoverished the soul of the Church in ways we cannot afford to ignore.

Stained glass is more than an art form; it is a sacred practice that embodies the Church’s call to engage all the senses in worship. By flooding sanctuaries with color and light, these windows transform otherwise ordinary spaces into places of awe and reverence. They invite worshippers to reflect on the mysteries of faith, to see the story of God’s redemption unfold before their eyes, and to experience the light of Christ illuminating their hearts and minds.

Our current trend toward utilitarian design, though often well-intentioned, risks flattening the worship experience. Sterile white walls and blank panes may serve a practical purpose, but they fail to inspire the imagination or stir the heart toward the divine. If worship is the highest act of the human soul, then the spaces in which we worship should reflect the glory, creativity, and transcendence of the God we serve.

The restoration of stained glass in our sanctuaries is not simply about aesthetics; it is about reclaiming a theological vision for beauty. The Church has always understood that art can be a means of drawing the soul closer to God. Just as music lifts our souls in praise and the spoken Word instructs our minds and pierces our hearts—stained glass engages our vision, helping us to behold the glory of God in a uniquely powerful way.

Moreover, stained glass windows remind us of the communal nature of our faith. These windows were often created through the collaboration of artisans, theologians, and patrons, embodying the collective devotion of the Church. Their narratives, depicting the lives of saints and the overarching story of Scripture, connect us to the universal and timeless body of Christ. In a fragmented and individualistic age, such reminders are more necessary than ever.

To restore the art of stained glass is to restore a sense of the sacred to our spaces of worship. It is to acknowledge that worship is not merely functional but formational—that the beauty of our surroundings shapes our hearts and minds as we encounter the beauty of God. It is to reject the sterile and embrace the sublime, to lift our eyes from the mundane and fix them on the eternal.

As I reflect on my time in the Arctic Warrior Chapel, surrounded by the vibrant story of Scripture in radiant color and light, I am reminded of how deeply those windows drew me into the story of the Lord’s redemptive work. What if our sanctuaries today could once again be places that inspire such awe? What if they could serve as catechisms in color, drawing us closer to the God of light and beauty?

The art of stained glass is not a relic of the past—it is a gift for the Church today and for generations to come. While the Church is ultimately the people of God, these vibrant works of art reflect the beauty of the bride of Christ, portraying in light and color the incredible reality of what the Lord has done, what He continues to do, and what He will ultimately accomplish to bring about her glorification in Him. As the light shines through these windows, illuminating the craftsmanship upon them, let them remind us that this is precisely what the Light of the Lord does when it shines through us—it reflects the beauty of His workmanship in our lives. Let us not allow this gift to fade into history. Let us instead reclaim it, filling our sanctuaries with the kind of beauty that lifts hearts and stirs imaginations with radiant reminders of the God who is the true source of all beauty, truth, and life.

Erwin Panofsky, Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures (Princeton University Press, 1979).

G. R. Evans, The Church in the Early Middle Ages (I.B. Tauris, 2007).

Elizabeth Denio, Symbolism in Christian Art and Architecture (G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1895).

Otto von Simson, The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order (Princeton University Press, 1988).

Panofsky, Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures, 49.

Rolf Toman, Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting (Ullmann Publishing, 2015), 208.

Jane Brocket, The Little Book of Stained Glass Windows (Frances Lincoln Publishers, 2019), 17.

Toman, Gothic, 215.

Paul Binski, Medieval Craftsmen: Glass-Painters (University of Toronto Press, 1991), 9.