Wrestling With God: The Limits of Psychological Pragmatism and the Truth of the Gospel

As a chaplain, I can’t tell you how many of my soldiers come to me and ask, “Chaplain, what’s your take on Jordan Peterson?” It’s a question I hear often, and I always approach it with a sense of gratitude. For many of these young men and women—some who have never opened a Bible before—Peterson’s lectures or his writing have stirred a curiosity about Scripture and a longing to understand its relevance. In an age where many people seem increasingly disinterested in faith, it’s remarkable to see a cultural figure drawing people back to the Bible. I thank God for the conversations this has sparked, the questions it raises, and the doors it opens to speak about matters of eternal importance.

But as excited as I am about this renewed engagement with the Bible, I find myself wrestling with an unease. Peterson’s work, while brilliant and insightful in many ways, stops short of the kind of “wrestling with God” that truly changes the human heart. His interpretation of Scripture often focuses on how its stories can improve lives in the here and now—how they help us find meaning, order, and responsibility in a chaotic world. These are good and necessary pursuits, and many people have testified to how his ideas have helped them make better decisions or overcome personal struggles. Yet, as deeply practical as his insights are, they lack the power to deal with what Scripture itself identifies as the deepest human problem: our estrangement from God.

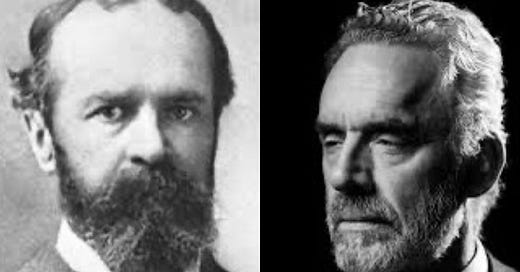

Peterson’s pragmatic approach to the Bible resonates strongly with another influential thinker: William James. Over a century ago, James championed the idea that the truth of religious belief is found in its ability to “work”—to bring peace, stability, and moral transformation. Both James and Peterson see religion not primarily as a matter of divine revelation but as a psychological tool for human flourishing. And while this perspective has its merits, it also limits what religion—especially Christianity—is ultimately about. Faith is not just about improving lives; it’s about saving souls. The Bible is not merely a guide for life; it’s the story of God’s redemption.

This distinction is not a minor one. It is the difference between seeing the Bible as an artifact of human wisdom and recognizing it as the living and active Word of God. It is the difference between using faith as a means to a better life and surrendering to the truth of Christ for eternal salvation. Peterson and James encourage people to engage with religion on a deeply personal and meaningful level, but their frameworks fall short of the transformative power that comes from being confronted by God Himself.

As I reflect on the renewed interest in faith sparked by these thinkers, I am both encouraged and burdened. Encouraged, because the questions they raise are leading many back to Scripture. Burdened, because the answers they provide, while insightful, stop short of the ultimate truth the Bible proclaims. In this brief article, I want to explore the contributions of William James and Jordan Peterson to our understanding of religious belief and the Bible. I will examine some their insights and appreciate the ways they challenge a culture often indifferent to matters of faith. But I also want to consider where their perspectives fall short and point instead to the greater truth Scripture offers: a God who calls us not to a mere wrestling with meaning, but to a wrestling with Him—a wrestling that leads not just to a better life, but to eternal life.

William James: Faith as a Lifeline for the “Sick Soul”

William James, one of the most influential thinkers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, approached religion with a singular question: what practical difference does it make in a person’s life? For James, the value of religious belief was not found in proving its metaphysical truths but in demonstrating its tangible effects. In his landmark work, The Varieties of Religious Experience, James examined religion as a profoundly personal phenomenon, focusing on how it functioned in the lives of individuals, particularly those grappling with despair and brokenness.

James was a pioneering voice in the philosophy of pragmatism, a framework that evaluates truth not by its correspondence to reality, but by its utility. For James, an idea is “true” insofar as it “works”—if it brings coherence, stability, and purpose to a person’s life. Religion, he argued, is “true” for those who experience it as a means of overcoming life’s challenges, even if its doctrines remain unverifiable or subjective.

This perspective allowed James to sidestep debates over the existence of God or the historical accuracy of religious texts. Instead, he focused on religion’s fruits—its ability to transform lives, inspire moral behavior, and provide existential relief. While James did not deny the possibility of God’s existence, he treated it as a secondary question. What mattered most to him was whether belief in God made life better for those who held it.

One of James’ most compelling insights is his description of the “sick soul.” Unlike those with a sunny disposition who find life inherently meaningful, the sick soul is profoundly aware of the world’s brokenness and their own inner turmoil. For these individuals, life is characterized by despair, guilt, and a sense of alienation from the good. It is religion, James argued, that offers a lifeline to such souls, providing hope and a means of reconciling their divided selves.

James cataloged numerous examples of religious transformation, from dramatic conversions to the slow and steady development of faith. He marveled at how belief could bring peace to the restless, strength to the weak, and moral clarity to the confused. For James, these transformations were evidence of religion’s power and its necessity for human flourishing.

James’ work remains valuable for several reasons. First, he highlights the deeply personal nature of religious belief, emphasizing its role in addressing the existential crises that every human being inevitably faces. His concept of the sick soul resonates with anyone who has felt the weight of their own inadequacy or the brokenness of the world. Second, James reminds us that faith has a practical dimension—it is not merely an intellectual exercise but something that profoundly shapes how we live and relate to others.

Furthermore, James’ openness to the diversity of religious expression is both challenging and refreshing. He avoided reducing religion to a single system of thought, instead acknowledging its varied and often contradictory forms. For James, the value of faith lay not in its uniformity but in its ability to meet people where they are and lead them toward wholeness.

Yet, for all its insights, James’ pragmatic approach to religion has significant limitations. By focusing exclusively on the utility of faith, he sidesteps the question of its truth. Is God real? Are the teachings of Scripture trustworthy? James avoids these questions, seeing them as secondary to the psychological and moral benefits religion provides.

This reluctance to engage with the metaphysical claims of Christianity creates a troubling ambiguity. If religion is “true” because it works, does this mean all religions are equally valid, regardless of their claims about God or salvation? And if faith is only useful as long as it produces certain results, what happens when a believer encounters suffering or doubt that faith cannot immediately resolve?

Ultimately, James’ framework reduces religion to a tool for human flourishing, ignoring its deeper purpose. Faith is not simply a means of coping with life’s challenges; it is a response to the God who reveals Himself as Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer. While James recognizes the transformative power of religion, he stops short of affirming its ultimate source and goal.

Christianity does not merely invite us to find purpose and peace; it calls us to embrace the truth of God’s revelation and to surrender our lives to Him. Faith is not just about what works—it is about what is true. And it is in this truth, not merely in its utility, that the power of the gospel is found.

Jordan Peterson: The Bible as Archetypal Wisdom

Peterson has emerged as one of the most influential cultural thinkers of our time, particularly among young people who feel adrift in a chaotic world. His lectures and writings have captivated audiences, especially his engagement with the Bible. For Peterson, the Bible is not just a historical or religious text but a profound repository of archetypal wisdom—a collection of stories that reflect the deepest truths about human nature and the structures necessary for a meaningful life.

At the core of Peterson’s approach to Scripture is his reliance on Carl Jung’s concept of archetypes—universal patterns of thought, behavior, and narrative that emerge repeatedly in human culture. Peterson views the Bible as the most comprehensive and enduring compilation of these archetypes. The stories within it, from Cain and Abel to the Exodus, are not primarily concerned with historical or theological truth but with psychological truths. They reveal how humans have learned to confront suffering, order chaos, and live responsibly in a fallen world.

Peterson frequently describes the Bible as “metaphorically true.” This means that while its stories may not be factually accurate in a literal sense, they carry truths that resonate universally. For example, the story of Cain and Abel, according to Peterson, illustrates the destructive power of envy and resentment. The Flood narrative symbolizes the necessity of confronting life’s chaos and finding renewal through moral responsibility. These stories, Peterson argues, endure because they speak to the fundamental struggles of human existence.

A recurring theme in Peterson’s interpretation of the Bible is the struggle between chaos and order, a dynamic he sees as central to human life. He identifies chaos with the unknown, the unpredictable, and the destabilizing forces of existence, while order represents stability, structure, and meaning. For Peterson, biblical stories often reflect this tension, offering blueprints for how individuals and societies can navigate it.

Take the story of the Garden of Eden. Peterson sees this not as an account of humanity’s literal origins but as an archetypal narrative about the loss of innocence and the birth of self-consciousness. Adam and Eve’s fall symbolizes humanity’s awareness of its own vulnerability and moral responsibility, themes that continue to define the human condition. Similarly, the Tower of Babel illustrates the dangers of pride and the fracturing of community when individuals or groups pursue power without humility.

These interpretations resonate deeply with Peterson’s audience, particularly those searching for meaning in a world that often seems fragmented and aimless. By framing the Bible as a guide for navigating the complexities of life, Peterson makes its stories accessible to a generation more familiar with psychological frameworks than theological ones.

Peterson’s engagement with the Bible has had a profound cultural impact, particularly in its ability to draw secular and skeptical audiences into a serious consideration of Scripture. Many of his listeners, having never opened a Bible before, find themselves captivated by the richness of its narratives and the practical wisdom it offers. In an age increasingly marked by relativism and cynicism, Peterson’s insistence that biblical stories contain timeless truths offers a compelling alternative.

Moreover, Peterson’s emphasis on responsibility and order resonates with those disillusioned by the moral and existential ambiguity of modern life. He challenges his audience to confront their own chaos, to bear the burden of responsibility, and to align their lives with higher principles. These themes, rooted in his interpretation of Scripture, have inspired countless individuals to pursue personal growth and meaningful engagement with the world around them.

For all its insights, Peterson’s approach to the Bible is ultimately limited by its refusal to affirm the divine nature of Scripture. By focusing on the psychological and cultural utility of biblical stories, he reduces them to tools for human flourishing rather than revelations of God’s character and redemptive plan.

Peterson often describes the Bible as a “meta-narrative,” a grand story that provides a unifying framework for human existence. Yet this meta-narrative, in his interpretation, is not grounded in the historical reality of God’s actions but in the collective wisdom of humanity. For Peterson, the Bible’s authority lies not in its status as God’s Word but in its ability to shape individual and societal behavior. This leaves his hermeneutic incomplete, as it fails to address the Bible’s central claim: that it is the revelation of the one true God, who speaks and acts in history to redeem His creation.

Additionally, Peterson’s reliance on archetypes risks overshadowing the unique and specific message of the gospel. While archetypes can reveal universal truths, they cannot fully account for the particularity of Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection. The gospel is not merely an archetypal story of sacrifice and renewal; it is the historical proclamation of God’s victory over sin and death. To interpret it as metaphorically true is to miss its ultimate claim: that it is objectively and eternally true.

Jordan Peterson has done remarkable work in drawing people back to the Bible and encouraging them to wrestle with its significance. His interpretation of Scripture as a source of archetypal wisdom offers valuable insights into the psychological and existential depth of its stories. Yet, as compelling as Peterson’s approach may be, it falls short of recognizing the Bible’s ultimate purpose. The Scriptures are not merely tools for personal and societal order; they are the living Word of God, revealing His redemptive plan and calling us to worship and trust in Him.

Peterson challenges us to confront the chaos of life and align ourselves with higher principles, but the Bible calls us to something far greater: to be reconciled with the Creator through the person and work of Jesus Christ. While Peterson’s work has opened doors for many, the true power of the Bible lies not in its archetypal wisdom but in its proclamation of the gospel—the good news of salvation for all who believe.

Beyond Utility

James and Peterson rightly recognize that faith and the Bible hold immense power to transform lives. Both highlight how belief systems and biblical stories shape individuals and societies, providing meaning, order, and purpose. But as insightful as their perspectives are, they stop short of the full picture. Faith in Christ is not merely valuable because it “works.” The gospel is profound, not because it offers helpful metaphors for navigating life, but because it actually happened.

Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 15 confront us with the ultimate question of truth: Did Jesus Christ rise from the dead? Writing to believers in Corinth, Paul declares, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins” (1 Cor. 15:17). For Paul, the resurrection is not an archetype or a symbolic narrative—it is a historical reality. And if that reality is false, the entire Christian faith collapses. “If in Christ we have hope in this life only, we are of all people most to be pitied” (1 Cor. 15:19).

This passage exposes the central limitation of psychological pragmatism: it cannot bear the weight of Christianity’s ultimate claims. If religion is only valuable because it “works,” then it is no better than a placebo. Its usefulness may improve lives temporarily, but it cannot address humanity’s greatest need—the need for redemption, reconciliation, and eternal life. The gospel’s power lies not in its ability to teach us moral lessons or offer archetypal wisdom, but in the fact that it proclaims a Savior who lived, died, and rose again in real history.

James and Peterson point to the Bible as a source of meaning, and in some sense, they are right. Scripture has inspired individuals, shaped cultures, and sustained hope in the darkest times. But what has changed lives for the past 2,000 years is not the Bible’s literary beauty, its moral teachings, or its psychological insights. What has changed lives is the person at the center of the story—Jesus Christ.

It was not the metaphor of the cross that transformed Paul from a persecutor of Christians to an apostle of Christ. It was the risen Lord who appeared to him on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:1–6). It was not the archetypal power of the resurrection that turned fearful disciples into bold witnesses; it was the empty tomb and their encounter with the risen Jesus (John 20:19–29). The gospel does not call us to admire a story, but to trust a Savior who conquered sin and death and now reigns as King.

The resurrection is the cornerstone of Christianity, and it is profoundly different from the symbolic truths James and Peterson focus on. If the resurrection is merely a metaphor for hope or renewal, it cannot save us. But because the resurrection is a historical event, it has the power to change everything. It assures us that Christ’s death truly atoned for sin, that death itself has been defeated, and that all who trust in Him will share in His victory (1 Cor. 15:54–57).

The Bible’s ultimate purpose is not to make us better versions of ourselves or to help us find meaning in life. Its purpose is to reveal God—to confront us with His holiness, His justice, His love, and His redemptive plan for humanity. It calls us not to mere admiration but to worship. Faith is not about aligning ourselves with archetypes or moral frameworks; it is about surrendering to the living God who has acted in history to save sinners.

This is where James’ and Peterson’s frameworks fall short. By reducing religion to utility, they place the focus on us—on what we need, what we experience, and how we can flourish. But the gospel is not fundamentally about us; it is about God. It is about His glory, His purposes, and His invitation to be reconciled to Him through Christ.

The Bible does not invite us to wrestle merely with meaning but with God Himself. Like Jacob wrestling with the angel in Genesis 32, true faith comes when we encounter God in a way that humbles us, transforms us, and leaves us dependent on His grace. It is not enough to extract psychological or moral wisdom from Scripture. We must come face-to-face with the Author of Scripture, who calls us to repent, believe, and follow Him.

Why the Truth Matters

The distinction between utility and truth is not an abstract theological debate; it is a matter of eternal significance. If the resurrection is true, then Jesus Christ is Lord, and every person must respond to Him. If it is false, then even the best moral teachings of the Bible are ultimately meaningless. The stakes could not be higher.

Paul understood this when he wrote, “But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep” (1 Cor. 15:20). Because the gospel is true, it offers not just temporal hope but eternal life. It does not merely help us cope with the chaos of this world; it promises a new creation where sin, suffering, and death will be no more (Revelation 21:4).

William James and Jordan Peterson have helped many rediscover the Bible’s relevance and power, and for that, I am deeply thankful. Their insights into the psychological and cultural dimensions of religion remind us of the Bible’s richness and enduring significance. But their approaches fall short of the ultimate truth the Bible proclaims. The gospel is not a metaphor or an archetype; it is the declaration of what God has done in Christ to redeem a fallen world.

As I think about the soldiers who come to me, drawn to Peterson’s ideas and curious about faith, I am filled with hope. These conversations are opportunities to point them beyond utility to truth, beyond archetypes to Christ. My prayer is that they—and all of us—will not stop at wrestling with meaning but will go further to wrestle with God Himself. For it is in that wrestling that we find not just a better life, but a new life, rooted in the unshakable reality of the gospel and the Savior who has changed the world forever.

Brilliant

Thank you for this fine essay. I love your analysis of the situation and appreciate how you credit Peterson and James with the good they do bring to the discussion. It shows respect for their work and their lives. In the end, I know that the Word of God is so powerful that anyone opening it has the possibility of encountering the living Lord and having a true interaction - a wrestling - with him.