The Revolution in Rhyme

How Poetry and Song Inspired and Mythologized the American Revolution

In the dim light of colonial taverns, the air was thick with the hum of conversation, the clinking of tankards, and the fervent recitation of verse. Poets and patriots stood shoulder to shoulder, weaving words into weapons sharper than any sword. Their poems and songs became rallying cries, uniting disparate colonies under a shared vision of liberty and rebellion. Where muskets and cannons waged war on the battlefield, the pen and the tongue waged a parallel fight for hearts and minds. Poetry, with its rhythm and rhyme, carried revolutionary ideals into the homes, streets, and souls of a budding nation.

The American Revolution was not won solely by force of arms but also by force of imagination. Revolutionary poets and songwriters transformed the struggle for independence into an artistic crusade, crafting verses that exalted liberty, denounced tyranny, and called colonists to action. Satirical poems mocked King George III, while stirring songs like “The Liberty Song” and “Yankee Doodle” echoed through taverns and encampments, binding communities together in shared defiance. Even the simplest rhyme could convey profound truths, sparking debates, inspiring courage, and cementing the ideals of freedom into the national psyche.

Poetry and song fueled the American Revolution, from biting satire to heartfelt rallying cries. These literary forms were not mere ornamentation but essential tools in shaping public opinion, fostering unity, and sustaining morale. Through their enduring verses, we see how the revolutionaries wielded words as weapons, proving that the pen—and sometimes the song—is mightier than the sword.

Poetry as Revolutionary Propaganda

Long before muskets cracked and cannons roared, the war for independence began in the minds of the American colonists. In this battle for hearts and convictions, poetry served as a critical weapon, delivering revolutionary ideals in a form that resonated deeply with both the learned and the common folk. These verses were more than words on paper; they were calls to action, reminders of injustice, and celebrations of liberty. Revolutionary poets gave voice to a movement that was as much about ideology as it was about territory.

Phillis Wheatley, the first published African American poet, used her pen to articulate the moral and philosophical foundations of liberty. In her poem “To His Excellency General Washington,” she exalts the fight for freedom and praises Washington as a heroic leader: “Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side, Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.”

Wheatley’s work provided not only inspiration but also a moral legitimacy to the revolutionary cause, framing it as a fight aligned with divine justice. Her words were a testament to the universal yearning for liberty, transcending race and class. Wheatley, like so many other African Americans during the Revolution, believed the cup of liberty would overflow upon them with the victory of the American cause. Unfortunately it would be nearly a century later and a bloody Civil War that would help begin the process of finally bringing those liberties to them.

Another significant voice was Mercy Otis Warren, whose biting satires and patriotic verses galvanized public opinion. In her poem “The Squabble of the Sea Nymphs,” Warren mocked British leaders, portraying them as inept and corrupt. Her sharp wit made the British government a target of ridicule and rallied colonists to stand firm in their opposition. “Satire, when truth is its aim,” Warren once wrote, “strikes with a force more potent than the cannon’s roar.”

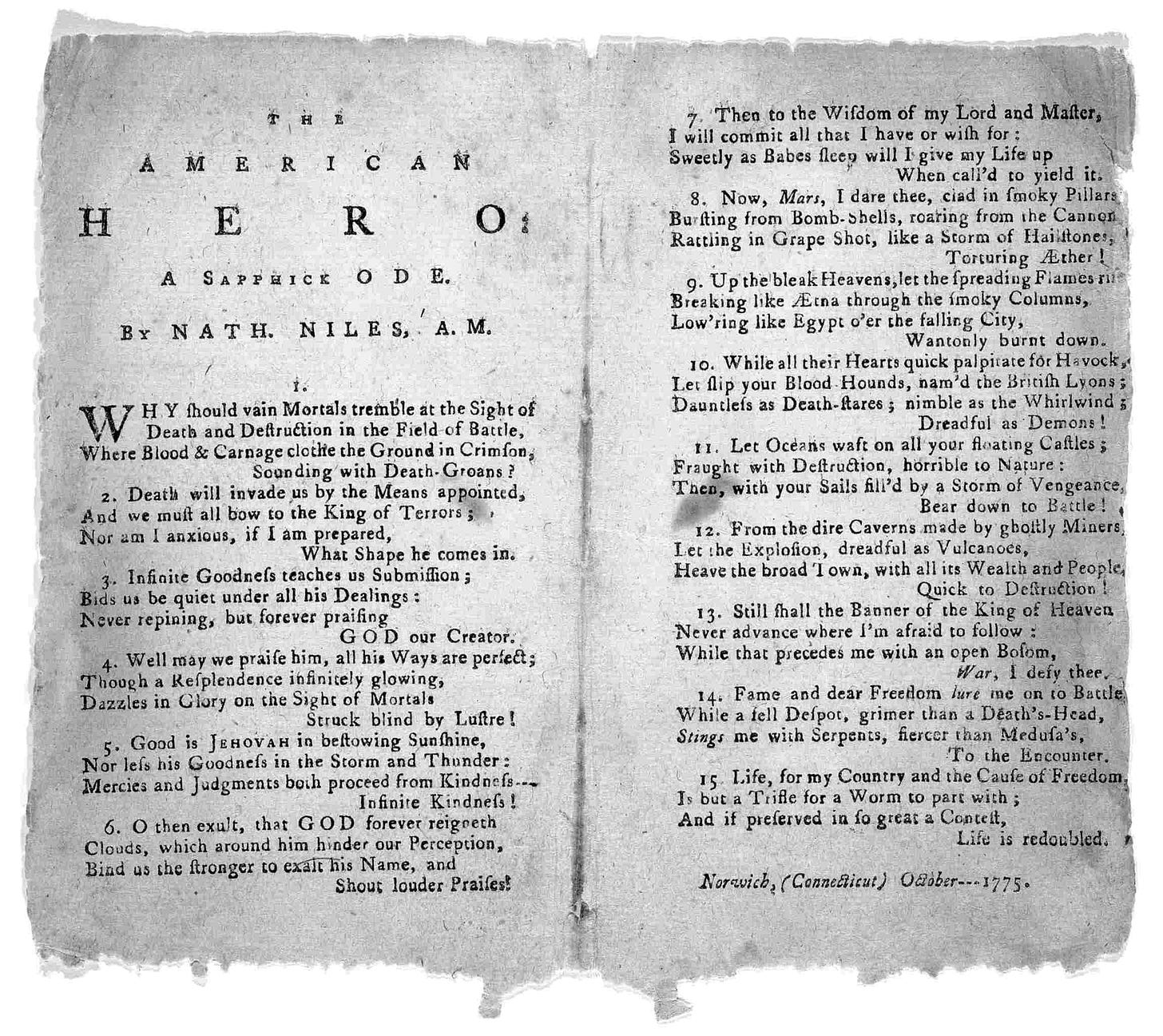

Nathaniel Niles contributed to the cause with his poem “The American Hero,” a stirring tribute to the courage of the colonial militia. His verses painted the soldiers as virtuous defenders of liberty, enduring hardship for a righteous cause:

“Thus with united hearts and hands, Together linked, a firm, unshaken band, Boldly they march, their banners wave on high, Resolved to conquer or resolved to die.”

Niles’ work served not only as encouragement to the troops but also as a reminder to civilians of the sacrifices being made on their behalf. His vivid imagery turned the abstract ideals of freedom into a tangible, human struggle.

Through poetry, these writers communicated revolutionary ideas in a way that pamphlets or speeches could not. The rhythm and emotion of their verses captured the imagination of the colonies, igniting passions and inspiring action. The simple yet profound themes of liberty, justice, and the fight against tyranny reverberated in taverns, meeting halls, and homes. As the revolution gained momentum, poetry became a unifying force, giving words to the dreams of an emerging nation.

Poets like Wheatley, Warren, and Niles understood that the battle for independence was as much a cultural and ideological struggle as it was a military one. Their words fortified the resolve of their compatriots and ensured that the revolution was not only fought but also felt. Through their verses, the pen proved mightier than the sword, cutting through the doubts of the wavering and rallying the faithful to the cause of liberty.

Satire and Ridicule: Mocking the Crown

While poetry celebrated liberty and rallied colonists to action, it also served another purpose: deflating the power of the British Crown through satire and ridicule. Colonial poets recognized that humor could be a potent weapon, one capable of exposing the absurdities of tyranny while uniting people through shared laughter. Where earnest calls to action stirred hearts, biting satire targeted pride, creating an atmosphere where British authority became not only despised but laughable.

Satirical poems often took aim at King George III, portraying him as inept, out of touch, and unworthy of loyalty. A popular broadside quipped:

“O George! Thou art a Monarch blind, As much to truth as laws inclined; Thy wrath has raised a direful storm, To blast thy crown, to change thy form.”

Such verses stripped away the mystique of monarchy, reframing the king not as a divinely ordained ruler but as a petty despot whose errors were fair game for ridicule. Lord North, the British Prime Minister, was also a frequent target. In one scathing verse, a poet lampooned his policies with brutal wit:

“Lord North, your plans are dark as night, And dim the torch of England’s light. But folly leads where wisdom’s flown, And sets the tempest on your throne.”

These poems resonated because they provided a shared outlet for colonial frustrations, encouraging solidarity through humor. They also invited ordinary colonists to see themselves as equals to their oppressors. By mocking British leaders, poets leveled the playing field, reducing figures of immense power to objects of derision.

Even Loyalists were not spared. Satirical verses mocked their allegiance to the Crown, often portraying them as sycophants or cowards. The poem “A New Song” jeered at Loyalists with the line, “To Tory hearts and British gold, Their slavish chains they dearly sold.”

Such jabs reinforced the idea that loyalty to Britain was not just misguided but shameful. These works emboldened colonists to distance themselves from the Crown and encouraged wavering individuals to join the revolutionary cause.

The effectiveness of satire lay in its ability to puncture the veneer of invincibility that surrounded British authority. By making the powerful look ridiculous, colonial poets created an environment where rebellion felt not only possible but inevitable. In the words of one anonymous writer: “The tyrant falls when fools deride, And liberty is magnified.” Through sharp wit and fearless critique, satire became a form of protest that reached beyond the battlefield, challenging British dominance with every cutting rhyme.

Songs of Freedom

Poetry may have stirred individual reflection, but it was song that united voices and hearts in a shared purpose. Revolutionary songs became the anthems of rebellion, resonating in taverns, rallies, and encampments, spreading the ideals of liberty far and wide. These melodies, often set to familiar tunes, carried messages of defiance and hope, reminding colonists of their common cause and bolstering their resolve.

Songs during the Revolution served as a form of mass communication, embedding the spirit of independence into the cultural fabric of the colonies. One of the earliest and most influential examples was “The Liberty Song,” written by John Dickinson in 1768. Sung to the tune of a popular British naval song, its refrain: “Then join hand in hand, brave Americans all, By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall”—became a mantra of solidarity, urging colonists to stand together against British oppression.

Another iconic song, “Yankee Doodle,” began as a British taunt, mocking the ragtag appearance of colonial militias. Yet, the colonists reclaimed the tune, transforming it into a triumphant declaration of resilience. Its biting humor turned the tables on British arrogance, as later verses celebrated American victories:

“And there was Captain Washington Upon a slapping stallion, A-giving orders to his men— I guess there was a million!”

Such songs were more than entertainment—they were tools of persuasion, rallying cries that spread revolutionary fervor from cities to the most remote corners of the colonies.

The power of these songs lay in their ability to bring people together, transcending social, regional, and even linguistic divides. Singing in groups fostered a sense of camaraderie and collective purpose, reminding colonists that they were part of something greater than themselves. In taverns and at public gatherings, voices joined in unison, harmonizing not only melodies but also ambitions for a free and independent nation.

The act of group singing was itself a form of resistance. By participating, colonists declared their allegiance to the cause and their rejection of British rule. Songs like “The Liberty Song” and “Chester” by William Billings—a favorite of revolutionary congregations—gave voice to their hopes for a brighter future:

“Let tyrants shake their iron rod, And slavery clank her galling chains, We fear them not, we trust in God, New England’s God forever reigns.”

The universality of these songs ensured that even those who could not read revolutionary pamphlets could still participate in and internalize the movement’s ideals.

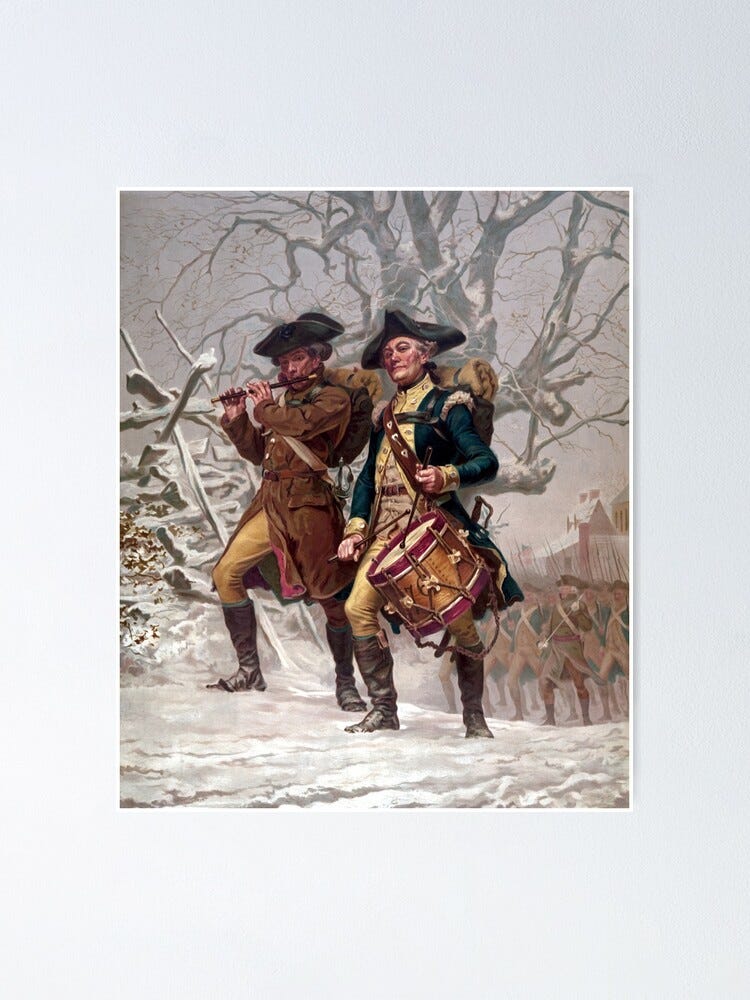

On the battlefield, songs became a source of morale, boosting the spirits of soldiers as they marched into uncertain and often dire circumstances. Troops would sing to drown out fear, inspire courage, and remind themselves of the righteousness of their cause. For soldiers, these songs offered psychological reprieve in the face of danger. They reinforced the belief that their sacrifices were not in vain and that their efforts were part of a larger, divine plan for freedom. Singing together also strengthened bonds among troops, creating an unshakable sense of brotherhood essential for enduring the hardships of war.

Even off the battlefield, patriotic music resonated with citizens, keeping the revolutionary spirit alive during long and trying campaigns. It reminded them of the stakes of the fight and the potential for victory, no matter how distant it seemed. As one soldier reportedly said of his comrades’ singing, “The music was worth more than a thousand reinforcements.”

Through song, the Revolution found its pulse—a rhythm that carried the cause forward and resonated in the hearts of colonists. These melodies not only united and inspired but also instilled a confidence that liberty was within reach. As the colonists sang their defiant tunes, they transformed their struggle into a symphony of freedom, one that still echoes through the annals of American history.

Romanticizing the Revolution

The American Revolution did not end with the signing of the Treaty of Paris or the departure of British troops. Its spirit endured, woven into the fabric of the young nation through the poetry and songs that defined its struggle. These works became more than rallying cries for liberty; they transformed into cultural artifacts, shaping the collective memory of the Revolution and romanticizing its ideals for generations to come.

Revolutionary poems and songs, preserved in broadsides, pamphlets, and journals, remain vital windows into the emotions and aspirations of the era. These works reflect the raw sentiment of a people fighting for their freedom, capturing the fear, hope, and triumph that defined the Revolutionary War.

As these poems and songs were passed down, they cemented the Revolution as not merely a historical event but as a foundational myth of justice and determination. The poetic and musical traditions of the Revolution laid the groundwork for future movements for justice and equality. Abolitionists in the 19th century drew upon Revolutionary language, intertwining their cause with the ideals of liberty and equality expressed in Revolutionary poetry. Hymns like “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” reflected the enduring legacy of patriotic music while challenging the nation to live up to its promises.

Poetry also played a central role in the civil rights movement, where verses and songs once again became rallying cries for a fight against oppression. The Revolutionary spirit of defying tyranny echoed through the decades, as leaders invoked the same ideals of freedom to address the injustices of their own time. Revolutionary poetry, with its themes of courage and perseverance, provided both inspiration and a reminder of the transformative power of art in shaping public will.

Perhaps the greatest impact of Revolutionary poetry lies in its role in mythologizing the American Revolution. Poets and songwriters, even years after the war’s conclusion, cast the Revolution in heroic terms, painting it as a nearly divine struggle for liberty. In doing so, they elevated the war beyond mere historical conflict, presenting it as the ultimate triumph of good over evil.

The simplicity and emotional resonance of these works played a key role in creating this mythology. Through verse, the Revolution became a story of virtuous farmers and merchants rising against a cruel and oppressive empire. This romanticization shaped the way Americans understood their own history. The Revolution, as told through poetry and song, became a moral victory, a story of destiny fulfilled. It inspired not just patriotism but a belief in America’s unique role in the world as a beacon of freedom. Even today, these works evoke the same pride and reverence, their melodies and rhymes still capable of stirring hearts.

Through the preservation of its poetry and songs, the Revolution lives on as a story of hope and defiance. These works immortalized the ideals of the war, influencing not only subsequent movements for justice but also the way Americans remember their origins.

“Let history keep her faithful pen, And sing the deeds of freedom’s men. For in their words, their voices ring, Eternal truth shall ever sing.”

By transforming the Revolution into verse, poets ensured that the fight for liberty would never fade into obscurity, but instead remain a living testament to the enduring power of art in shaping the identity of a nation.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Verse

The American Revolution was a battle of muskets and cannons, but it was also a war of words. Revolutionary poetry and song played a vital role in inspiring people to action, giving voice to their deepest aspirations for liberty, justice, and unity. Through rhythm and rhyme, poets turned abstract ideals into rallying cries that could be carried in the hearts and minds of ordinary colonists. In taverns and town squares, on battlefields and around campfires, these works created a shared sense of purpose, reminding all who sang or recited them that their fight was not in vain.

But the influence of this verse did not end with the war. It transformed the Revolution itself into a living mythology, elevating it from a historical event to a moral narrative—a struggle for universal truths that would echo through the centuries. Poetry romanticized the Revolution, shaping America’s understanding of its origins and its identity as a nation uniquely committed to the cause of liberty. The words of Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and countless anonymous poets turned soldiers and farmers into symbols of courage and righteousness, ensuring that their sacrifices would be remembered not just as victories of arms but as triumphs of the human spirit.

Revolutionary verse also left an enduring legacy on the way Americans approach moments of crisis and change. From abolition to civil rights, the rhythms of liberty have continued to inspire movements for justice, proving the timelessness of the ideals expressed in those early songs and poems. In every generation, words have had the power to awaken the soul of a people, to remind them of who they are and what they stand for.

Ultimately, the American Revolution taught us that the pen and the sword are not mutually exclusive. Verse was not merely a reflection of the war but an active participant, moving the colonists from despair to defiance and from defiance to action. It inspired them to believe not just in the possibility of freedom, but in its inevitability. And in doing so, it transformed a people into a nation.

As we reflect on the role of poetry in the Revolution, we see that its true power lies in its ability to stir both hearts and histories. For through verse, the memory of the Revolution is not static—it sings. And as long as it sings, it reminds us that the fight for liberty is not just the story of our past, but the song of our future.

For Further Reading

Aldridge, Alfred Owen. The Ironic Temper and the Comic Imagination. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969.

Breen, T.H. American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People. Hill and Wang, 2010.

Davidson, Cathy N. Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America. Oxford University Press, 1986.

McDonnell, Michael A. The Politics of War: Race, Class, and Conflict in Revolutionary Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Niles, Nathaniel. The American Hero: A Sapphick Ode. Boston: E. Draper, 1775.

Phelps, Glenn A. Mercy Otis Warren and the American Revolution: Rhetoric, Gender, and Politics. University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Shields, David S. Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America. University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. Vintage, 1993.

Zagarri, Rosemarie. Revolutionary Backlash: Women and Politics in the Early American Republic. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.