The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come

The Power of Repentance and the Belief in Redemption

I recently sat down with my son to watch the animated version of A Christmas Carol featuring Jim Carrey as Ebenezer Scrooge. It’s a movie I’ve seen countless times in various forms, but sharing it with my kids gave it a fresh perspective. As the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come emerged, its shadowy, faceless form towering over the screen, my son turned to me, eyes wide, and said, “That one’s the scariest, Dad.” I couldn’t argue with him. There’s something chillingly visceral about that third ghost. It doesn’t speak, doesn’t gesture with warmth or invite understanding. It points. Cold, deliberate, unrelenting. It embodies the void—the inevitable end—and leaves Scrooge, and us, trembling.

I believe there’s a very important reason this ghost is the most haunting of the spirits, even more than Marley with his rattling chains or the Ghost of Christmas Past with its piercing, all-seeing gaze. The third ghost is terrifying because it is silent, final, and unflinching in the face of Scrooge’s desperate pleas. It offers no comfort, only a stark confrontation with what might be—a future unredeemed by change. Watching my son process that fear, I realized anew the profound depth of Dickens’s story. This ghost doesn’t just terrify; it provokes. It challenges us to consider our own lives, our own futures, and the specter of what might become of us if we remain unchanged.

Dickens’s genius in A Christmas Carol is his ability to intertwine horror with hope. Scrooge begins the story as the very embodiment of miserliness and self-inflicted isolation. He is a man who has forfeited his humanity for profit, who sees people not as souls but as costs or benefits on a ledger. In the opening scenes, we meet a man who scoffs at generosity, dismisses the poor as expendable, and mocks the very spirit of Christmas. Scrooge is not just a miser in material terms; he is impoverished in spirit, his soul barren and cold. And yet, Dickens allows us to see that even this man, this hardened, bitter creature, is not beyond redemption.

The arrival of the spirits is more than a plot device; it is an act of grace. Each ghost represents an opportunity for Scrooge to see himself clearly—past, present, and future. The first two spirits, while unsettling, offer glimpses of light. The Ghost of Christmas Past takes Scrooge back to a time when he knew joy, love, and connection. It shows him the innocence of his youth and the slow erosion of his heart as greed and self-preservation took over. The Ghost of Christmas Present reveals the vibrant life he is missing: the joy of Fred’s laughter, the warmth of the Cratchit household, and even the silent dignity of Tiny Tim’s faith in the face of suffering. These visions are painful, but they are also hopeful. They suggest that Scrooge’s life, though misspent, still contains the seeds of goodness.

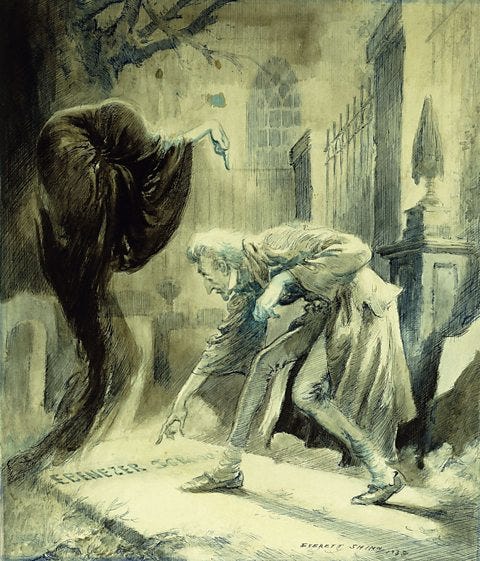

But the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is different. It is not a guide; it is a judge. It points, unrelenting, to the inevitable consequences of Scrooge’s choices. The imagery here is stark and unflinching. We see the Cratchit family mourning Tiny Tim’s death, the once-vibrant household subdued by grief. We see Scrooge’s own death, marked not by sorrow or remembrance but by apathy and relief. His belongings are stolen and sold by those who cared nothing for him in life. His gravestone is the final blow: a silent marker of a wasted existence, a man remembered for nothing and loved by no one.

What makes this vision so powerful is its immediacy. Dickens doesn’t allow us to distance ourselves from Scrooge’s fate. As the ghost points to the gravestone, Scrooge’s terror becomes our own. Who among us has not wondered how we will be remembered? Who has not feared that our lives might ultimately count for nothing? The ghost’s silence is the most profound part of its message. It doesn’t argue or explain. It merely shows, leaving Scrooge—and us—to grapple with the weight of what we see.

What struck me as I watched this with my son was how Dickens uses this moment to force a confrontation with repentance. Scrooge’s terror is not just about death; it is about judgment. It is about standing face-to-face with the undeniable truth of a life lived selfishly and the irrevocable consequences that follow. In theological terms, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come is a shadow of the final judgment, the moment when all pretense falls away, and we are left with the bare reality of who we are. It is a moment of conviction, and conviction, while terrifying, is also the prelude to transformation.

What makes A Christmas Carol so enduring is that it doesn’t leave Scrooge in despair. His confrontation with the ghost is not the end but the turning point. As he falls to his knees, begging for the chance to change, we see the birth of repentance—not the shallow regret of one caught in wrongdoing, but the deep, soul-wrenching realization of a life lived in opposition to love. Scrooge’s cry, “Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me,” is the heart of the Gospel message: the hope that even the worst among us can be redeemed.

When Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning, the transformation is nothing short of miraculous. His joy is infectious, his generosity boundless. He becomes the antithesis of the man we met at the beginning of the story. This isn’t a superficial change; it is a rebirth. Scrooge has seen the truth of his life, and it has utterly undone him. But in being undone, he is made new. Dickens doesn’t just show us a man who becomes kind; he shows us a man who embraces life with a vigor and joy that can only come from the realization of grace.

As I reflected on this, I found myself asking what the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come might reveal about my own life. Have I allowed the love of Christ to transform me, or are there still parts of my heart that cling to selfishness and fear? Do I live with the awareness that my choices today shape the legacy I will leave behind? Watching Scrooge’s transformation, I was reminded of Paul’s words in 2 Corinthians 5:17: “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come.” Scrooge’s story is, at its core, a parable of redemption. It reminds us that no one is beyond the reach of grace and that true repentance leads to a life overflowing with generosity, love, and joy.

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in 1843, during a time when industrialization and economic disparity were at their height. The story is deeply rooted in social critique, challenging the greed and indifference of Victorian England. Yet its themes are timeless. In every age, we are tempted to prioritize wealth, comfort, and self-interest over the well-being of others. In every age, we risk forgetting the power of generosity to transform lives—both ours and those we touch.

One of the most important details that makes Dickens’s tale so profound is its insistence that transformation is possible. Scrooge is not doomed by his past, and neither are we. The Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come shows us the shadows of what might be, not what must be. It leaves room for hope, for the possibility that we, too, can change. This is the essence of the Christmas message: that Christ came not to condemn the world but to save it, to offer light in the darkest places and life where there was only death.

As the credits rolled and my son curled up next to me, I thought about the simple wisdom in his observation. The third ghost is indeed the scariest, but it is also the most necessary. Without it, Scrooge’s transformation would lack urgency. Without the confrontation with his own mortality, he might never have realized the depth of his need for change. And without repentance, there can be no redemption.

In the end, A Christmas Carol is more than a holiday story, it is a call to examine our lives, to confront the ways we have fallen short, and to embrace the grace that allows us to begin again. It is a reminder that Christmas is not just a season of giving but a celebration of the greatest gift of all: the chance to be made new.

It’s passages like these that place the book miles ahead of any of its adaptations (many of which I love):

"horror and hope"...very well put. I love "A Christmas Carol" but always felt that the resolution was too swift relative to the way Dickens expounds upon all else that he introduces in the short work. However, I never considered that the swiftness is on account of one's experience with Grace, an experience which is sure to leave one "undone." What's more, in abruptly ending the narrative of Scrooge, we readers, left wondering as to what is next, must consider for ourselves how to "honor Christmas in [our] hearts, and try to keep it all year."