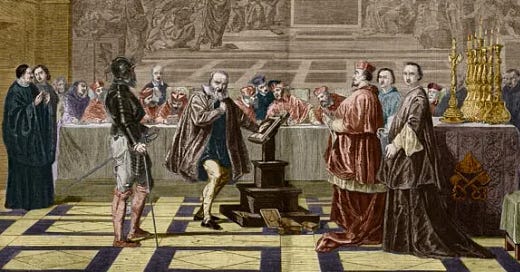

Galileo’s Trial

The Problem of Oversimplification and the Necessity of Nuanced Historical Research

On this day in 1633, Galileo Galilei was put on trial for charges of heresy. The trial of Galileo is often portrayed as the quintessential clash between science and religion, primarily focusing on his advocacy for the Copernican heliocentric system, which posited that the Earth revolves around the Sun. This oversimplified narrative serves more as a mythic representation of the conflict between emerging scientific evidence and established doctrine. However, a closer examination of the historical and contextual factors reveals that the trial was the culmination of a complex interplay of personal vendettas, political tension, and theological subtleties, rather than solely a dispute over heliocentrism.

One significant aspect often overlooked is the role of personal vendettas against Galileo. He was not only a brilliant scientist but also a man known for his sharp tongue and tendency to ridicule those who disagreed with him. This personality trait earned him many adversaries within the academic and ecclesiastical establishments. For example, his satirical work, "The Assayer," mocked the Jesuit mathematician Orazio Grassi's work on comets, indirectly offending the Jesuits, a powerful group within the Church who initially supported his astronomical findings.

Most Galilean researchers today agree that politics played a much bigger role than religious closed-mindedness, but there is spirited disagreement about the specifics. Some think the pope was angry at being parodied by Galileo's character Simplicius in Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems. Other scholars have suggested that church leaders felt Galileo had tricked them into granting him a license to write the book by not revealing its Copernican leanings.

Another argument by some scholars is that in the middle of the Thirty Years' War the Tuscan Duke of Medici had refused to aid Rome in its war efforts against France. Pope Urban VIII decided to punish the Duke by arresting the Duke's personal friend, Galileo. These personal conflicts set the stage for his later confrontation with the Church.

The timing of Galileo's trial also coincided with a period of intense political tension due to the Counter-Reformation. The Catholic Church was at the height of its campaign to reform itself and fight Protestantism, which had challenged papal authority and led to significant religious fragmentation in Europe. In this context, the Church was particularly sensitive to any challenges to its authority, including from within its ranks. The support of heliocentrism, seen as contradicting the Scriptures, was perceived not just as a scientific stance but as a potential threat to the Church's doctrinal authority.

The Church did not initially oppose heliocentrism outright. In fact, Copernican theory was discussed and studied by many Jesuit astronomers and mathematicians without immediate condemnation. The critical turning point came when Galileo sought to reinterpret Scripture based on his scientific observations.

This accusation of “reinterpreting of Scripture” was drawn from Galileo’s response to criticism of his Copernican views in a December 1613 Letter to Castelli. In his letter, Galileo argued that the Scripture--although truth itself--must be understood sometimes in a figurative sense. A reference, for example, to "the hand of God" is not meant to be interpreted as referring to a five-fingered appendage, but rather to His presence in human lives.

Given that the Bible should not be interpreted literally in every case, Galileo contended, it is senseless to see it as supporting one view of the physical universe over another. "Who," Galileo asked, "would dare assert that we know all there is to be known?" Galileo hoped that his Letter to Castelli might foster a reconciliation of faith and science, but it only served to increase the heat. His enemies accused him of attacking Scripture and meddling in theological affairs.

Cardinal Robert Bellarmine, a key figure in Galileo's trial, emphasized that heliocentrism could be discussed hypothetically but insisted that advocating it as an undeniable truth that contradicted the Scriptures without irrefutable evidence was unacceptable. Galileo's inability to provide such incontrovertible proof (for instance, the stellar parallax, which was not observed until much later due to the limitations of telescopic technology of the time) played a crucial role in his trial.

The Catholic Church banned Galileo's 1632 book Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, forced Galileo to recant his heliocentric views and condemned him to house arrest. He died in his Florence home in 1642.

Conclusion

The trial of Galileo was not merely about heliocentrism but was a multifaceted event influenced by Galileo's personal conflicts, the political climate of the Counter-Reformation, and theological debates over scriptural interpretation. This complexity suggests that the trial cannot be reduced to a simple narrative of science versus religion. Instead, it was a pivotal moment that highlighted the tensions between emerging scientific paradigms and established ecclesiastical authority, influenced by a confluence of personal, political, and theological factors.

By reducing historical events to easily digestible narratives, we risk missing the essence of these events—how they were shaped by their context and, in turn, how they shaped future developments. Nuanced historical research allows us to move beyond these binary oppositions and appreciate the complexity of past events. Historical research that appreciates context provides a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of events, reflecting the interconnectedness of social, political, and intellectual movements.

Galileo’s trial offers lessons for contemporary discourse on the relationship between science and religion, authority and inquiry, and tradition and innovation. It reminds us of the importance of critical thinking and the dangers of dogmatism. In an era where information is abundant and narratives are often polarized, the need for careful, nuanced analysis of issues is more pressing than ever.

As we delve into the past, let us strive for a comprehensive understanding that respects the intricacies of human endeavor. In doing so, we not only honor the richness of history but also equip ourselves with the insight to navigate the complexities of the present and future.